While preparing a lecture for IADT students on Memory and Archives, I decided take a look back through some old research folders. I came upon a presentation I gave at the American Comparative Literature Association (ACLA) conference at Utrecht University in 2017, as part of a panel on Diffractive Pedagogies. It was organised by Prof. Iris van der Tuin and colleagues at Utrecht University. It’s an example of me, magpie-like and post-PhD, trying to make sense of what I’m doing by framing my research-creation practice within concepts or theories that other communities are working with, in this case New Materialisms. I don’t entirely feel at peace with this habit, and I’m learning how to describe what I’m doing on it’s own terms, in a more simple way hopefully. Nevertheless, it is fascinating to work with different concepts and to read ones practice through those concepts, as a way to see new associations and patterns. And it’s useful, within ones practice, for opening up thought and conversation with others in different contexts, academic or otherwise.

Engineering Fictions as Diffractive Pedagogy | Dr. Jessica Foley

Today, I want to give an account of a mode of diffractive pedagogy at work through a telecommunications research centre called CTVR, where I made my PhD thesis. Firstly, I’m going to give an outline of how I am coming to understand the meaning of diffraction; secondly, I’m going to speak about the context of my PhD research as an apparatus of diffraction, and thirdly I’m going to introduce an experiment called Engineering Fictions, devised during my PhD research, as one mode of diffractive pedagogy. I’m sticking to this script so that I can convey all this within the time, I hope you will bear with me!

diffraction

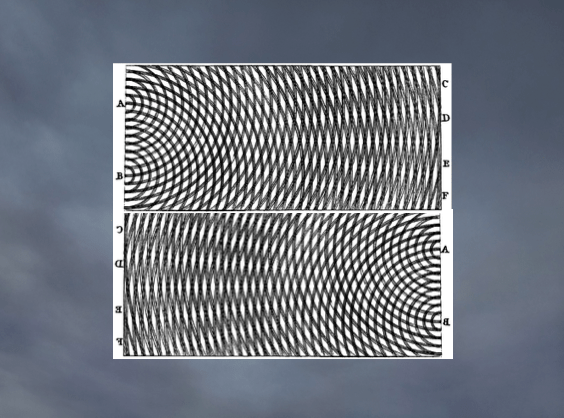

The concept of diffraction comes from physics. Along with reflection, refraction and interference, diffraction is a name given to the properties of light. In her 2014 article, Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting Together Apart, feminist physicist Karen Barad outlines the early story of diffraction, beginning in the mid-17th century and with the work of Francesco Grimaldi, who had begun experiments that would catalyse the field of optics.

From his observations on the effects of light passing through a pinhole into a darkened room, Grimaldi conceptualised light in a different way, as fluid-like rather than corpuscular. He observed that as light encounters objects it breaks up and moves outwards in different directions, and he called this diffraction. In what was possibly the earliest laboratory produced two-slit experiment to map diffraction patterns, Grimaldi’s notes reveal his observations of this remarkable feature of light:

“That a body actually enlightened may become obscure by adding new light to that which it has already received.” (Barad, 2014)

Barad theorises the two-slit experiment as an apparatus that changes how we conceive of light and dark. She says that the experiment;

“…queers the binary light/darkness story. What the pattern reveals is that darkness is not a lack. Darkness can be produced by ‘adding new light’ to existing light – ‘to that which it has already received’. Darkness is not mere absence, but rather an abundance… Diffraction queers binaries and calls out for a rethinking of the notions of identity and difference.”(Barad, 2014)

The phenomenon of diffraction introduced a conception of material doubleness, contradiction, and paradox into what had seemed like a more or less stable physical world, as described by classical physics.

But for Karen Barad, “diffraction owes as much to a thick legacy of femnist theorizing about difference as it does to physics”. Adapted from a scientific model, as the organisers of this seminar have articulated, diffraction has been re-turned figuratively as an analytic tool that can help to generate “dynamic, non-linear method(s) of reading and writing in which stable epistemological categories are challenged, temporalities are disrupted and disciplines are complexified” (van der Tuin et al. 2014).

For feminist scientist and theorist Donna Haraway;

“Diffraction is a mapping of interference, not of replication, reflection or reproduction. A diffraction pattern does not map where differences appear, but rather maps where the effects of difference appear” (Haraway, 2004).

Diffraction as a methodology, for feminist scholars at least, has become synonymous with methodologies for dismantling patriarchal structures and regimes of repression, oppression and domination. This approach is exemplified at this conference in the work of filmmaker Trin T. Minh-ha, who has continually troubled notions of identity and difference defined through colonizing logics of privilege and exclusion.

For Minh-ha the concept of difference functions as a “tool of creativity to question multiple forms of repression and dominance” and not as “a tool of segregation, to exert power on the basis of racial and sexual essences” (Barad, 2014).

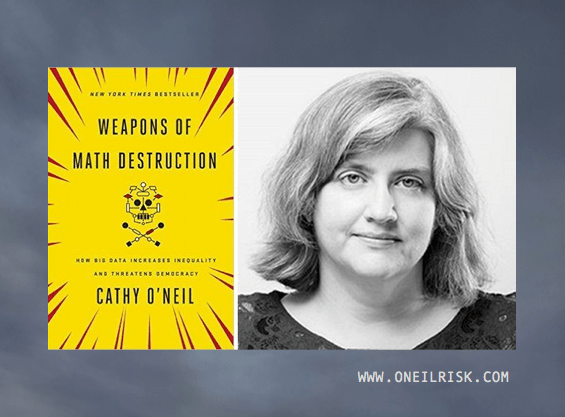

Such a philosophy of difference becomes re-vitalized at time when we see colonial logics subtly propagating to nano and algorithmic scales in networked computing devices and interfaces. I’m thinking here of the work of mathematician Cathy O’Neil who has set up her own company as an algorithm auditor, and of Joy Buolamwini who has established the Algorithmic Justice League.

CTVR as an APPARATUS OF DIFFRACTION

Minh-ha’s characterization of difference-as-double speaks to the context of the research experiment I wish to share with you today.Minh-ha’s insight on how difference can operate as a critical, creative tool and as a tool of segregation and the assertion of repressive power speaks to me of the challenges facing interdisciplinary research today, particularly at the intrafacing boundaries of creative arts practices, science, engineering and technology.

For the past number of years, I have been working as an artist along the boundaries of this disciplinary millieu. And I often find myself asking: What place does creative arts practice have in the context of mainstream telecommunications research? Why should such practices, seemingly so different to the science and engineering of communications technologies and to academia more generally, be operational within this space? There are many ways to respond to these questions, but I will offer an answer today that responds with the concept of diffraction.

The Centre for Telecommunications Value-Chain Research, CTVR for short, was the context where I developed a PhD thesis in collaboration with engineering researchers. CTVR was a centre where optical, wireless and antenna engineering researchers worked, sometimes collaboratively, sometimes cooperatively, to devise and build communications networks. The kinds of knowledges and expertise colluding in the centre typically related to physical and computer sciences, engineering, mathematics, as well as to education and administration, business and industry.

I came to work in this centre more or less by chance, through an encounter with its Director, Prof. Linda Doyle. On paper, Linda was a communications engineer. Her research focused on a specialist field called Cognitive Radio and Software Defined Radio. Through this research she had become involved with questions of Electromagnetic Spectrum Policy and Management,and the general political economy of the medium of ICT Networks.

For various reasons, in addition to her own research and directing CTVR, it fell to Linda to ensure that activities in relation to Education and Outreach were happening within the centre. Linda wanted to do something different to the usual school visits, targetting young people and enthusing them about careers in STEM. Her interest in education was of a radical and feminist tradition, informed by an activists attention toward power relations. She was not interested in reproducing stale habits of outreach that seemed to address the imperatives of a status quo economy.

Linda was interested in the practice and politics of art and architecture, in particular the work of modernist designers Charles and Ray Eames, and she wanted to find a way to bring this ‘extra-curricular’ interest into the mainstream of the centre and engineering education more broadly.

This ongoing gesture of mingling creative arts and pedagogical practices with engineering research enacted a concept of difference as a tool of creativity and questioning. While I was not the first artist to develop research through CTVR, I was the first to engage directly with the Centre as both subject and collaborator.

The question that compelled what became my PhD research was one Linda posed rhetorically many times: How can we Communicate Communications? I took this question seriously, allowing it to catalyse a diffractive process of questioning through my encounters and relations with CTVR’s researchers and staff. I began modelling ways of communicating not because of, but in spite of my perceived ‘occupational’/segregational difference as ‘artist.’ As Audre Lorde would say, I had to take my difference and make a strecngth of it as a critical and creative tool, not a segregational or exclusive one. There was always a danger that the deeper task of communication would be internally delegated as the sole privilege and responsability of the artist, and not as a common currency of research culture.

Over time, I began to conceptualise CTVR’s desire to communicate differently. The gesture of ‘smuggling’ creative arts practitioners into the space of telecommunications research was a way of modelling a more generous concept of difference and how difference might critically enrich the centre’s culture of research. I saw this desire not strictly as an externally oriented or outreach-driven one, but also as an internally oriented or inreach-driven desire. Through my PhD research, therefore, I began developing a process I named inreach.

This process involved learning, incrementally and through trial and error, how to convene experiments that could open up possibilities for CTVR’s researchers and guests to critically and creatively inhabit together the question of communicating communications. This kind of approach is what curator and theorist Irit Rogoff has called ‘embodied criticality,’ and it is an effect of practices of ‘smuggling,’ or what we might understand here as an effect of diffraction.

Thus, thinking with feminist theorists, makers and activists such as Minh-ha, Barad, Haraway, van der Tuin and, indeed, Linda Doyle, I have come to think of CTVR as a diffraction apparatus, a rambling house of diversifying epistemological cultures and practices, where differences began to generate processes of creative response-ability and communication.

CTVR became an in-between place where, as one colleague punned: “we make waves”.

Engineering Fictions as diffractive pedagogy

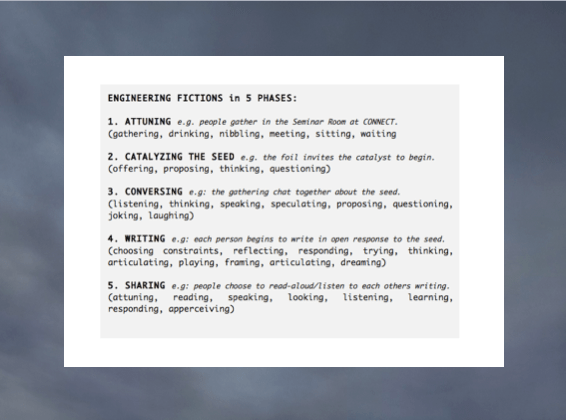

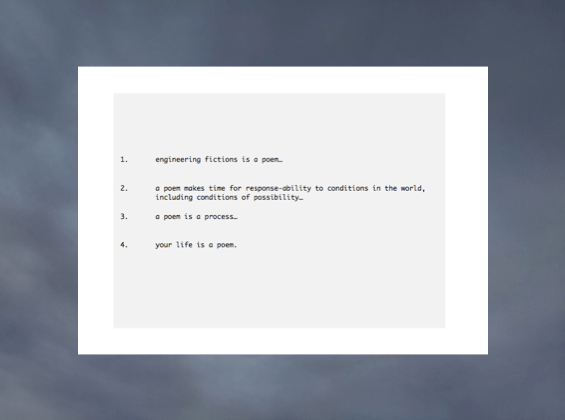

So, now I want to introduce you to one of the experiments I devised with/in CTVR, called Engineering Fictions. At its most simple, Engineering Fictions was a topic led, conversation and writing session which took place once or twice a month with/in CTVR, over a number of years.

I’m passing around a prototype box-set of postcards. Each postcard holds the score of an Engineering Fictions session from 2013. I intend to add the subsequent years sessions to this set.

These scores began as propositions and were largely produced orally and contingently over time through CTVR. It was only much later that the propositions were written down, becoming scores after the event. Unfortunately, these postcards cannot show the processes of improvisation and surprise often evoked in the lead up to and during each session, but hopefully they offer some insight into the topics of each session.

Engineering Fictions generated an in-between space where the function and act writing as communication was at stake. Albeit a gross simplification, I think it is fair to say that the expectation of writing, in the context of CTVR, was that it should, as Trin T. Minh-ha describes, “communicate, express, witness, impose, instruct, redeem, or save – at any rate to mean and send out an unambiguous message.”

Writing, as a ‘communication’ practice, was often assumed to be modelled as an information event, described best by Claude Shannon’s ingenious mathematical theory. Minh-ha names this kind of assumption as the effect of a ‘Vertically Imposed Language.’ Under such conditions, Minh-ha asserts, writing becomes “reduced to a mere vehicle of thought and may be used to orient toward a goal or to sustain an act, but it does not constitute an act in itself.” Engineering Fictions began as a creative compulsion, on my part, to generate space for writing that assumed a map other than the ‘vertically imposed language’ described by Minh-ha.

Through each session the proposition of another kind of map was made with those from the research centre, who gathered voluntarily. This map, described by Minh-ha as “perfectly accessible but rife with paradox… for its intent lies outside the realm of persuasion,” was one that afforded a different kind of access to the question of communicating communications.

The sessions offered periods of time where topics of a more general concern to CTVR’s researchers; topics such as ‘limits’ and ‘misunderstanding’ and ‘symmetry’ and ‘cognitive radio’; could be diffractively explored through writing ‘outside the realm of persuasion’.

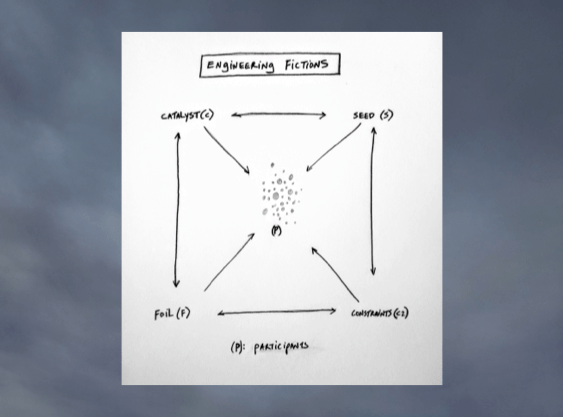

The diagram on screen is an attempt to map out the various players and movements in this experiment. (Ad lib a description here – then move on to describe the phases of the sessions)

If Engineering Fictions can be understood as an experiment in diffractive pedagogy, where epistemological categories and habits of communication are subtly destabilised and disrupted, and where the discipline of engineering becomes complexified, then the writings generated during the sessions can be understood, in Haraway’s words, as “maps where the effects of difference appear”.

Thinking with Trinh T. Minh-ha, I theorize that Engineering Fictions established a twilight practice of writing within CTVR which did not reinforce an opposition or binary-narrative between ‘vertical’ and/or ‘horizontal’ language. Instead, the sessions struggled to make space for writing both. Minh-ha describes twilight, entre chien et loup, as a time when identity becomes transformed, and I think this sense of time articulates her approach to diffractive pedagogy:

“It’s in that in-between space that something happens that is not yet known. Something happens in the space that is not yet defined, it has not a fixed name yet… it’s a question of two lights, two kinds of light. So you have daylight, you have nightlight. But instead of the opposition between day and night, you have something that leads from one kind of light to another kind of light. This kind of boundary is also very important in one’s own path. So you can say, for example that, in life, very often you encounter impasse; it can be political impasse, or it can be a spiritual impasse. But that impasse… may lead to be a passage. [Twilight] is a way of leading you to an elsewhere”

Engineering Fictions established a way of leading CTVR’s researchers (myself included) to an ‘elsewhere’ of communication and writing. This twilight experiment provided a time-space when different modes of speaking, listening, reading, writing, thinking and naming could take place. Engineering Fictions became a space for members and guests of CTVR to collectively inhabit and subtly transform the question of communicating communications through word and writing.

To conclude, I would like to share a piece of writing made during the final Engineering Fictions session of 2013 called The Talking Tombstone.

The catalyst for this session was Dr. Eve Olney, who opened up the topic of sound recording by considering how “the everyday encounter with a sound recording can alter both cultural and personal perceptions of time and our realtionship with the historical past.”

I would like you to read a short text (600 words) written during this session by engineering researcher Séamas McGettrick which he called Fragmented Voices in a Linear World (25th June 2013 Séamas McGettrick).

Fragmented Voices in a Linear World | Séamas McGettrick (25th June 2013)

Today’s talk made me think of a radio show I once listened to on NPR where the producer shared clips from an archive of a Colombian radio station that has a show that caters entirely for kidnapped victims. In our world’s march of endless progress we have created an unstoppable world that sounds more like myth than reality. A radio station that caters only for kidnapped victims, it seems surreal and odd. So today quite out of the blue when we started talking about recorded sound, linear, fragmented and geological time I started to wonder if this Colombian radio station and the experience people have because of it could be mapped into this concept of time.

The linear concept of time is probably the easiest time construct to apply to the situation because we are so used to time on a linear plane. The victims are taken from their families and brought to the jungle where they wait for weeks, months, years for a ransom to be paid or a dispute to blow over. The families in turn wait at home for word of their loved ones, a demand for money, the victim to walk through the door or the police to notify them of a body that has been found. These parallel time lines although mapping the exact same piece of time seem so far apart and I think that it is for this reason that radio station for kidnapped victims can exist. The family send messages on the radio to connect with their missing loved one to connect these two unstoppable time lines, likewise the victim listens out in the night to hear his beloved’s fragmented voice echoing across the airwaves to connect himself to his former reality. To know that a similar fate did not befall his family.

The messages recorded for the radio are fragmented time pieces. Messages recorded or broadcast live into the Jungle. Family members of the kidnapped queue for hours on important dates like birthdays or anniversaries (marriage or kidnapping) to record a little fragment to send to their loved one who may or may not receive it which is where I feel that geological time comes in. In cassette tapes this geologic time is the decay of the cassette but I feel that in the kidnapped radio example geologic time could refer to the decay of the radio signal as it arcs its finite hemisphere across the jungle canopy. The kidnap victims use long antennas to try to collect the weak signal as it decays and since they move around a lot (to avoid being found by authorities) there is no guarantee that just because you have the signal today that you will have it tomorrow.

I guess that means this example can be mapped to the linear, fragmented and geological time world. However I feel there is something more here. Maybe even a forth or fifth type of time that is to do with parallelism, hope and love. I can’t reconcile that a simple concept of linear time can include two such different experiences that are so alien to each other. Is linear time a deeply personal experience in which case it is not merely linear, but a huge parallel track with many junctions as our time lines cross. Also how does fragmented and geologic time manage to connect points on a linear time line. For this to happen in linear time present must be connected to past in a linear way. Or is there something else at work here? Do all points connect to a higher point in a higher dimension. Is this a simple fold in the fabric of space time? Or is it God?